Wall Street Journal, By Alyssa Abkowitz

June 06, 2014

It’s the kind of investment that might be a little uncomfortable to discuss at cocktail parties, but it’s a favorite in the higher-end spheres of family offices and hedge funds: capitalizing on shortages in world-wide resources.

Such scarcities, real or imagined, make headlines all too often these days. And investment firms say trying to jump on anticipated shortages (or prevent them) remains an overlooked strategy for high-end investors with funds and patience. The examples are many, from investing in sound technology that detects leaks in pipes, to buying into a mine in Idaho that may bear millions of metric tons of phosphorus, an obscure mineral critical to many products. And so are the success stories.

London-based Impax Asset Management, for example, which focuses on investing in resource scarcity and has investments in precision irrigation pipes and water-treatment systems, reported a 415 percent leap in assets for the BNP Paribas Aqua fund it manages. At the end of 2013, the fund had $706 million in assets under management, compared with $137 million a year earlier. “The more profitable place to play is in resources efficiency, not in raw materials,” says Ominder Dhillon, head of distribution at Impax.

Cashing in on resource scarcity—and, in turn, resource efficiency—is an area highly sensitive to the spurts and sputters of everything from rising population changes to the recent slowdown in emerging markets. At the moment, technology that moves and uses resources more effectively is a hot area. Kleinwort Benson Investors, for example, has been managing assets related to water since 2000 and currently has $1.5 billion in assets under management in its environmental strategy, which has outperformed the MSCI World Index in 11 years of the firm’s 13-year tenure. In 2013, the firm’s water-strategy portfolio was up 32 percent.

To be sure, timing investments in shortages can be difficult. During the financial crisis, for example, prices of copper peaked in the spring of 2008 as investors rushed in on the so-called shortage. By the fall of 2008, copper prices had dropped 40 percent.

One of the most alluring markets continues to be the supply of clean, drinkable water. Though water covers roughly 70 percent of the earth, only 2.5 percent of it is deemed fresh. One of the largest water plays, which represents as much as 50 percent of some water-strategy portfolios, is infrastructure—everything from the pipes, pumps and valves that deliver water to homes, to the drainage systems for storm water, to the irrigation systems for crops. Raúl Pomares, the senior managing director at Sonen Capital, which is based in San Francisco and whose clients include family offices, says water-resource efficiency has become a large theme for the firm, making up about 20 percent of its public equity strategies.

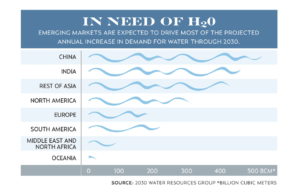

In emerging markets such as Asia, where about 23 percent of the world’s wealthiest investors now reside, countries need new infrastructure to bring clean water to growing cities. China Everbright International, the environmental arm of China’s state-owned China Everbright Holdings, invests in and operates wastewater-treatment plants in China and is a favorite among some wealth-management firms. “All those people need wastewater to be treated and carried away,” Dhillon says. “There’s a long-term growth theme.” Other investors are interested in water-infrastructure stocks like Sulzer, a Swiss pump manufacturer, which have the potential to grow earnings in a variety of markets, says Steve Falci, head of strategy development for sustainable investment at Kleinwort Benson, adding that a similar company, Wolseley, a distributor of plumbing and heating products, remains undervalued. Wolseley declined to comment on its stock values.

In places like the U.S. or the U.K., decades of underinvestment in pipe systems have made new pipe technologies whet the appetite of investors. Pure Technologies, a Calgary, Alberta-based company, has acoustic technologies that bounce sound waves off pipes to find which areas need repairs. Thomas Raymond of Abbot Downing, an ultra-high-net-worth wealth-management firm within Wells Fargo and based in Minneapolis, calls leak-detection services like these “low-hanging fruit.”

A less visible market is phosphorus, used in everything from fertilizer to toothpaste to each cell in our bodies. Some investors, including Jeremy Grantham, who oversees around $117 billion at Boston-based firm GMO, have sounded the alarm on the element—not because there isn’t enough of it right now, but because demand is expected to skyrocket, possibly leading to a shortage in as little as 20 years. What’s more, 85 percent of the world’s phosphate rock reserves are controlled by Morocco, which, Grantham says, “is an odd situation.”

Already, the tight power strings on phosphate have created price jumps. The stock price of Potash, a Canada-based company that mines phosphate, has increased nearly 17 percent in the past five years. In 2008, there was a short-term spike in phosphate rock prices, which rose 800 percent, in part because most countries that import the resource rely on only one or two countries that produce phosphate. What’s more, cheap and easy-to-access phosphate rock has been mostly used up, so the remaining rock is of lower quality and more expensive to mine, says Dana Cordell, research principal at the Institute for Sustainable Futures at the University of Technology in Sydney. “Cheap fertilizers have become a thing of the past,” she says.

Several companies are looking for new areas to mine phosphorus, since it can’t be duplicated in a lab. That includes Stonegate Agricom, which is based in Toronto and has two large phosphate projects under way: one located in Peru, and the other in Idaho. From the latter, the company expects nearly 17 million metric tons over the 19-year life of the mine, which could eventually lower U.S. phosphate imports. Production is scheduled to begin in the fourth quarter of 2014. The company says the Idaho project has the highest phosphate grade found in the Americas, which will eliminate the need for a processing plant and will lower operating costs.

In the end, the most efficient use of (and investment in) a scarce resource may be in recycling it. In Australia, the fifth-largest phosphate importer in the world, scientists are using remote sensing to find out exactly how much fertilizer crops may need for growth. And in Europe and the U.S., researchers are looking into ways of recycling phosphorus found in animal and human urine. Last year, for example, researchers at the University of Florida found they could extract 97 percent of the phosphates found in urine in about five minutes.

Says Cordell: “The wastewater industry is sitting on a gold mine.”

See the full story on the Wall Street Journal.